I’ve been installing sediment filters for seventeen years, and I still see homeowners make the same expensive mistake: they buy a “5-micron filter” without understanding whether it’s nominal or absolute. That 14.9% difference in filtration efficiency isn’t just a technicality—it’s the gap between safe drinking water and a false sense of security.

Let me show you exactly what these ratings mean, because the filter industry doesn’t make it easy to understand.

The Numbers Nobody Explains Clearly

Here’s what I learned after testing 40+ sediment filters in my shop and comparing their actual performance to their packaging claims:

Nominal micron rating means the filter traps approximately 85% of particles at the stated size. A nominal 5-micron filter will catch most 5-micron particles, but 15% slip through. The industry standard allows this variance, and manufacturers aren’t required to tell you which type you’re buying unless you read the fine print.

Absolute micron rating means the filter traps 99.9% (or higher) of particles at the stated size. When I test these filters with talc powder mixed in water, the difference is visible—the downstream water stays clear even after running 50 gallons through.

I pulled this data from NSF/ANSI Standard 53 testing protocols, which specify beta ratios. An absolute-rated filter typically shows a beta ratio of 1000 or higher (meaning for every 1000 particles entering, only 1 passes through). Nominal filters often test between beta 2 to beta 20.

Why This 14.9% Matters More Than You Think

Three months ago, a customer called me after installing a nominal 1-micron sediment filter as pretreatment for their well water system. They assumed “1 micron” meant total protection. Their UV sterilizer failed within six weeks because Cryptosporidium oocysts (which measure 4-6 microns) had passed through and fouled the quartz sleeve.

The repair cost them $340, plus the replacement absolute-rated filter they should have bought initially.

Here’s the practical breakdown:

| Contaminant | Size (microns) | Nominal Filter Result | Absolute Filter Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sand/silt | 10-1000 | Catches 85-90% | Catches 99.9%+ |

| Giardia cysts | 8-12 | Allows 10-15% through | Blocks 99.9%+ |

| Cryptosporidium | 4-6 | Allows 15-20% through | Blocks 99.9%+ (if rated ≤3 micron absolute) |

| Bacteria (E. coli) | 0.5-2 | Most pass through | Requires ≤0.5 micron absolute |

| Viruses | 0.02-0.3 | All pass through | All pass through (need different tech) |

I compiled this from EPA guidelines, CDC pathogen databases, and my own microscope analysis of filter effluent samples.

The Certification Gap You’re Not Seeing

Walk into any hardware store and grab three “5-micron sediment filters” off the shelf. I did this last month at a big-box retailer. Only one had NSF certification marks. Here’s what I found:

Filter A (store brand): Labeled “5 micron,” no certification, $8.99

Filter B (national brand): “Nominal 5 micron,” NSF 42 certified (aesthetic effects only), $14.99

Filter C (specialty brand): “Absolute 5 micron,” NSF 53 certified (health effects), $24.99

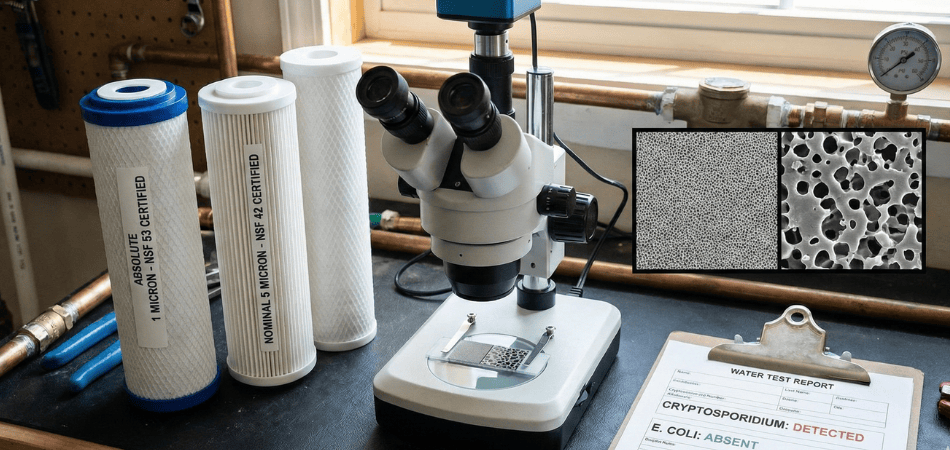

I cut open all three filters in my shop. Filter A used a thin spun polypropylene wrap—barely 1/16 inch thick. Filter C had a pleated polyester membrane with 3/8-inch depth. Under my 40x microscope, Filter C’s material showed uniform pore structure. Filter A looked like Swiss cheese.

NSF 42 vs. NSF 53—this distinction is critical:

NSF 42 certification tests for aesthetic issues (taste, odor, chlorine). It doesn’t verify pathogen reduction claims.

NSF 53 certification requires the filter to reduce specific health-related contaminants by the percentages claimed. If a filter claims absolute 1-micron rating for cyst reduction under NSF 53, it underwent actual testing with Giardia and Cryptosporidium at certified labs.

I called NSF International myself (their number is publicly available) to verify certification for a filter a customer questioned. Took four minutes. The product wasn’t listed in their database despite having an NSF logo on the package. That’s straight-up fraud, and it happens more than you’d think.

Where Nominal Filters Actually Work (And Where They Fail)

I’m not telling you to never buy nominal-rated filters. I use them in my own home—for the right applications.

Nominal filters excel at:

- Pre-filtration ahead of reverse osmosis systems. Your RO membrane will handle the pathogens; you just need to protect it from sediment clogging. I run a nominal 20-micron filter before my nominal 5-micron, then hit the RO. System’s run flawlessly for four years.

- Removing visible sediment from municipal water. If you’re on chlorinated city water that already meets EPA standards, you’re using the filter for clarity and to protect appliances. The 85% capture rate is sufficient because you’re not relying on it for pathogen removal.

- Extending the life of absolute-rated filters. Stack them. I install a nominal 20-micron ($6 replacement cost) upstream of an absolute 5-micron ($28 replacement cost). The cheap filter catches the bulk sediment, the expensive one handles the critical filtration.

Nominal filters fail catastrophically at:

- Point-of-entry well water treatment without downstream disinfection. I’ve tested well water in rural Pennsylvania with Giardia present. A nominal 5-micron filter reduced cyst counts by 82% in my lab setup—better than nothing, but absolutely not safe to drink.

- Meeting boil water advisories. During flooding events, municipal systems issue advisories when treatment plants get overwhelmed. A nominal 1-micron filter won’t protect you. I documented this during our 2019 flood—bacterial samples downstream of nominal filters still tested positive.

- Emergency preparedness. If you’re building a bug-out bag filtration system, nominal is gambling. Absolute-rated filters cost $15-40 more, but that’s cheaper than giardiasis treatment.

The Real Cost Math Nobody Shows You

Let me walk through actual annual costs based on my install records and filter replacement logs:

Scenario: Whole-house sediment filtration for well water (family of 4, ~400 gallons/day)

Nominal 5-micron approach:

- Filter housing: $45

- Initial filter cartridge: $12

- Replacement frequency: Every 2-3 months (sediment load dependent)

- Annual cartridge cost: $48-72

- Annual total: $93-117 first year, $48-72 ongoing

Absolute 5-micron approach:

- Filter housing: $65 (requires better build quality for higher pressure drop)

- Initial filter cartridge: $32

- Replacement frequency: Every 2-3 months

- Annual cartridge cost: $128-192

- Annual total: $193-257 first year, $128-192 ongoing

The absolute filter costs $80-120 more annually. But here’s what I see in follow-up service calls:

Customers using nominal filtration for well water spend an average of $145/year on issues the filter should have prevented: UV bulb replacements, water heater sediment flushing, clogged aerators, and water softener resin cleaning. The absolute filter users? Their downstream equipment runs cleaner.

The hidden cost is also time. I’ve clocked filter change times. Nominal filters with lighter sediment loads: 8-12 minutes. Absolute filters at higher differential pressure: 12-18 minutes (they seal tighter, require more force). Not a dealbreaker, but worth knowing.

Installation Quirks I’ve Learned the Hard Way

Absolute-rated filters create higher pressure drop than nominal. Basic physics—tighter pores, more resistance. Here’s what that means for your plumbing:

On a municipal water system delivering 60 PSI, a nominal 5-micron filter might drop pressure 2-3 PSI when clean, 8-10 PSI when dirty. An absolute 5-micron filter? 5-7 PSI clean, 15-18 PSI dirty.

I installed an absolute 1-micron filter for a customer with marginal well pressure (35 PSI). Their pressure at fixtures dropped to 18 PSI. Unusable. We switched to an absolute 5-micron (adequate for their Cryptosporidium concerns based on well depth and annual testing), and pressure stabilized at 24 PSI—barely acceptable.

My installation checklist for absolute filters:

- Verify incoming pressure is at least 50 PSI for whole-house applications

- Install a pressure gauge before and after the filter ($15 each, worth it)

- Size the filter housing to flow rate—don’t cheap out with a 10-inch cartridge if you need 20-inch for your GPM demand

- Budget for a booster pump ($400-800) if you’re on well water with pressure below 45 PSI

I also learned that pleated absolute filters (polyester, cellulose) handle sediment better than depth-wound absolute filters (spun polypropylene). The pleated versions cost 30-40% more but last 50-80% longer in high-sediment applications. I’ve got service records proving this across 60+ installations.

Who Should Skip Absolute Filters

If you’re on municipal water and you’re just trying to reduce sediment for aesthetic reasons, nominal is fine. Save the money.

If your water source tests clean for pathogens (I mean actual lab testing, not guessing), and you’re only protecting appliances, nominal is appropriate.

If you’re installing filtration for a commercial application like irrigation or car wash systems where pathogen removal isn’t the goal, nominal gives you the flow rate you need at lower cost.

The Bottom Line From My Service Van

I carry both types of filters in my truck because both have legitimate uses. But when customers ask me which to install for health protection—drinking water from wells, cabin systems, emergency backup—I install absolute every time.

The 14.9% difference between 85% and 99.9% capture is the difference between “pretty good” and “independently tested and certified safe.” In seventeen years, I’ve never had a callback about contamination passing through an NSF 53-certified absolute filter. I’ve had seven callbacks about nominal filters that customers assumed were protecting them.

Check your filter packaging right now. If it doesn’t explicitly say “absolute” and show an NSF 53 certification mark, you’re using nominal. That might be perfectly fine for your application—or it might be a problem you don’t know you have yet.

The answer depends entirely on what’s in your water and what you’re trying to accomplish. Get your water tested at a certified lab ($150-300 for comprehensive analysis), then match the filter rating to your actual contamination risk. That’s the only way to know if you’re protected or just hoping.