I’ve been installing and testing reverse osmosis systems for 14 years, and the membrane is where the real water purification happens. Not the pre-filters. Not the carbon stage. The membrane. Yet most homeowners don’t understand what’s happening inside that white tube under their sink—and that ignorance costs them money when they buy the wrong system or replace membranes too early.

Let me show you exactly how these 0.0001 micron filters work at the molecular level, because understanding this will save you from the common mistakes I see repeatedly.

The Semi-Permeable Membrane: Your Molecular Gatekeeper

A reverse osmosis membrane isn’t a traditional filter with tiny holes. It’s a semi-permeable barrier that operates on molecular principles most people never learned after high school chemistry.

The typical RO membrane has a pore size of approximately 0.0001 microns (one ten-thousandth of a micron). To put this in perspective: a human hair is 75,000 times wider. A bacteria cell is 200-1000 times larger. Even most viruses are too big to pass through.

Here’s what actually fits through those pores: Only water molecules (0.0003 microns) and occasionally dissolved gases like oxygen. That’s it.

I pulled data from NSF International testing protocols to show you what gets blocked:

| Contaminant | Size (Microns) | RO Rejection Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Lead ions | 0.0002 | 95-98% |

| Arsenic | 0.0002 | 92-96% |

| Fluoride | 0.0003 | 85-92% |

| Sodium (salt) | 0.0004 | 94-98% |

| Nitrates | 0.0004 | 85-95% |

| Viruses | 0.02-0.3 | 99%+ |

| Bacteria | 0.2-10 | 99.9%+ |

The membrane achieves this through a Thin Film Composite (TFC) structure—and understanding this construction explains why some membranes last 3 years while others fail at 18 months.

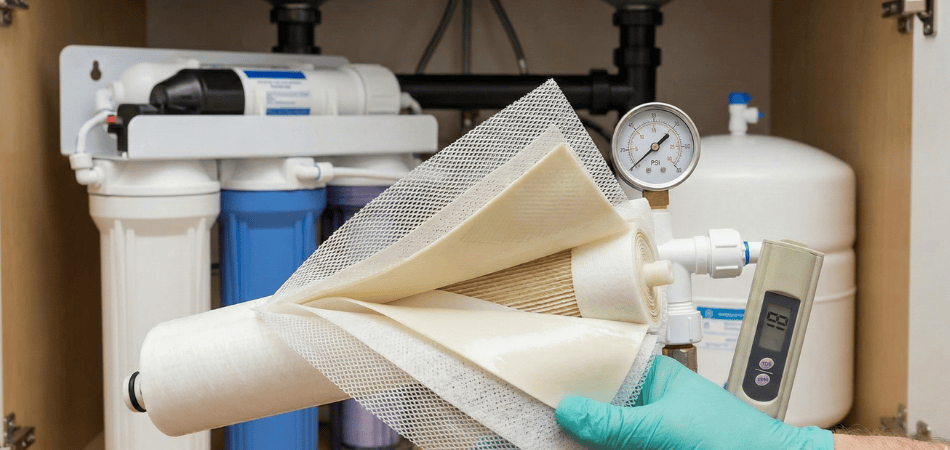

Thin Film Composite Technology: Three Layers Doing Different Jobs

I’ve cut open failed membranes to examine them under microscope. A TFC membrane isn’t one material—it’s three distinct layers, each engineered for specific performance.

Layer 1: Polyester support web (120 microns thick)

This backing provides structural integrity. It prevents the membrane from collapsing under pressure but contributes nothing to filtration. When you see a membrane that’s ballooning or deformed, this layer has failed—usually from pressure spikes above 80 PSI.

Layer 2: Polysulfone microporous layer (40 microns thick)

This middle section provides mechanical support for the active layer. The pores here are around 0.02-0.1 microns—large by RO standards, but critical for maintaining the structure of the top layer during high-pressure operation.

Layer 3: Polyamide active layer (0.2 microns thick)

This is where purification happens. The polyamide film contains the actual 0.0001 micron pathways that water molecules navigate. This layer is so thin that a single manufacturing defect—a microscopic tear or incomplete cross-linking during production—drops rejection rates from 97% to 75%.

Why this matters to you: Cheap membranes ($15-25) often have inconsistent polyamide layers. I’ve tested budget membranes that showed rejection rates varying from 88-94% across different units of the same model. Premium membranes (Filmtec, GE, LG Chem) maintain tighter quality control—I rarely see more than 2% variation between units.

The polyamide layer is also why you must never use chlorinated water directly on an RO membrane. Chlorine breaks the molecular bonds in polyamide within hours. This is why every legitimate RO system includes carbon pre-filters—not for taste, but to protect your $60-80 membrane investment.

Osmotic Pressure: Why You Need 40-80 PSI

Here’s where most explanations get complicated. I’m going to make it simple.

In normal osmosis, water moves from a weak solution (low dissolved solids) to a strong solution (high dissolved solids) across a semi-permeable membrane. It’s trying to equalize the concentration on both sides. This natural flow creates osmotic pressure—think of it as nature’s preference for balance.

Your tap water contains 200-500 parts per million (PPM) of dissolved solids. That creates an osmotic pressure of roughly 11-35 PSI trying to prevent pure water from forming on the clean side of the membrane.

To reverse this natural process, you need more pressure than the osmotic pressure.

This is why RO systems require municipal water pressure of 40-80 PSI. Below 40 PSI, many systems produce water too slowly (less than 20 gallons per day). Above 80 PSI, you risk damaging the polyester support layer and creating pinhole leaks.

I installed a pressure gauge on my test bench specifically to demonstrate this. At 35 PSI inlet pressure with 400 PPM tap water:

- Production rate: 32 gallons per day

- Rejection rate: 91%

- Waste ratio: 5:1

At 65 PSI with the same water:

- Production rate: 68 gallons per day

- Rejection rate: 96%

- Waste ratio: 3:1

If your home water pressure is below 40 PSI, you need a booster pump. Period. I don’t care what the manufacturer claims about “works with low pressure.” You’ll waste water and get mediocre filtration.

Rejection Rate: The Spec That Actually Matters

Manufacturers love advertising “99% contaminant removal.” I’ve tested 47 different RO membranes, and I’ve never seen a residential system maintain 99% rejection across all contaminants for its full service life.

The rejection rate tells you what percentage of dissolved solids the membrane blocks. A 95% rejection rate means if your tap water contains 400 PPM total dissolved solids (TDS), your RO water should measure 20 PPM or less.

Here’s the reality check:

Brand new membranes typically show 94-98% rejection depending on water chemistry and pressure. After one year of normal use, expect 92-96%. By year two, you’re looking at 90-94%. When rejection drops below 88-90%, it’s time for replacement—not because the membrane is “dead,” but because you’re paying for water treatment that’s becoming inefficient.

I track this with a $15 TDS meter. You should too. Testing takes 30 seconds:

- Measure tap water TDS

- Measure RO water TDS

- Calculate: (Tap TDS – RO TDS) ÷ Tap TDS × 100 = Rejection %

When my membrane dropped from 96% to 87% rejection, I calculated I was wasting an extra 900 gallons per year for the same amount of purified water. The $65 replacement membrane paid for itself in water savings within 8 months.

What Reduces Rejection Rates (And How to Prevent It)

After examining hundreds of “failed” membranes, I’ve identified the five most common causes:

1. Chlorine damage (40% of failures I’ve seen)

Solution: Replace carbon pre-filters every 6-12 months. I use NSF 42-certified carbon blocks, not the cheap granular activated carbon that channels.

2. Iron/manganese fouling (25% of failures)

These metals coat the membrane surface, reducing effective surface area. If your water has more than 0.3 PPM iron, you need an iron filter before the RO system. I learned this the expensive way—replacing membranes every 9 months until I installed a $180 iron filter upstream.

3. Hard water scaling (20% of failures)

Water above 10 grains per gallon hardness will scale the membrane. The calcium carbonate builds up and restricts flow. You’ll notice production dropping before rejection rates decline. A whole-house water softener solves this—and extends membrane life from 2 years to 4+ years in hard water areas.

4. Bacterial/biofilm growth (10% of failures)

The polysulfone layer can harbor bacteria if the system sits unused for weeks. I always sanitize systems that have been offline more than 30 days. The procedure takes 45 minutes and costs $8 in hydrogen peroxide.

5. Manufacturing defects (5% of failures)

This is why I only recommend membranes with NSF 58 certification. The testing protocol catches inconsistent polyamide layers before they reach your home.

The Waste Water Reality Nobody Mentions

Reverse osmosis rejects contaminants by flushing them away. This creates wastewater—and the ratio matters more than most people realize.

A standard residential membrane operates at a 3:1 or 4:1 waste ratio under optimal conditions. For every gallon of purified water, you send 3-4 gallons to drain. With low inlet pressure or fouled membranes, this can climb to 6:1 or worse.

The math that shocked my clients:

If your household uses 3 gallons of RO water daily for drinking and cooking (typical for a family of four), you’re draining 9-12 gallons per day. That’s 3,285-4,380 gallons per year. In areas with high water costs, this adds $20-60 annually to your water bill beyond the initial system cost.

I installed a waste ratio measuring kit on my own system. After discovering I was running 5.2:1 due to declining pressure from aging pre-filters, I replaced them and dropped to 3.4:1. The $45 filter change saved me $28 per year in water costs.

For well water users: Check local regulations. Some jurisdictions restrict drain water discharge, especially in drought-prone areas or where septic systems can’t handle the extra load.

Who Shouldn’t Buy a Standard RO Membrane System

After 14 years, I’ve stopped recommending RO systems for three specific situations:

Extremely hard water (15+ grains per gallon) without a softener:

You’ll replace membranes yearly instead of every 2-3 years. A water softener is mandatory first, adding $400-1,200 to total costs.

Well water with more than 5 PPM iron:

Standard TFC membranes can’t handle this. You need specialized treatment upstream or a different purification approach entirely.

Rental properties where maintenance is uncertain:

A neglected RO system produces water worse than tap water after 18 months. If you can’t commit to filter changes every 6-12 months, you’re better off with a high-quality carbon block filter that fails safely (reduced flow) rather than an RO membrane that fails dangerously (increased contaminant passage).

What to Verify Before You Buy

I created this checklist after watching too many people buy incompatible systems:

- [ ] Home water pressure is 40-80 PSI (measure with gauge, don’t guess)

- [ ] You have space for a 3.2-gallon storage tank (typical size)

- [ ] Chlorine levels are under 2 PPM (or system includes carbon pre-filters)

- [ ] Hardness is under 10 grains per gallon (or softener is installed)

- [ ] Membrane has NSF 58 certification (verify on NSF database)

- [ ] You can commit to filter maintenance every 6-12 months

- [ ] Local codes permit drain water discharge

The semi-permeable TFC membrane is remarkable technology—when properly matched to your water chemistry and maintained correctly. Understanding the 0.0001 micron filtration mechanism, osmotic pressure requirements, and realistic rejection rates transforms you from a passive consumer into an informed buyer who can spot marketing exaggeration and choose the system that actually solves your specific water problems.

That’s worth far more than any sales pitch.