You just invested in a whole-house water filter to improve your water quality, but now your morning shower feels like a drizzle. This is one of the most frustrating scenarios homeowners face after installation—and unfortunately, it’s also one of the most common.

After analyzing installation forums on Reddit’s r/Plumbing and reviewing dozens of pressure complaint threads on TerryLove.com, I’ve identified the five primary culprits behind post-installation pressure drops. More importantly, I’ll show you exactly how to diagnose which issue you’re dealing with using a simple pressure gauge test that takes less than 10 minutes.

The Pressure Drop Reality: What’s Actually Happening

Before we troubleshoot, you need to understand what “normal” looks like. According to the EPA’s water system standards, residential water pressure should range between 40-60 PSI at the tap. Any whole-house filtration system will cause some pressure reduction—that’s physics, not a defect.

The acceptable loss: A quality filter typically causes a 2-5 PSI drop when new and properly sized. If you’re experiencing drops of 10 PSI or more, or if your pressure has degraded over weeks rather than being immediately noticeable, you’re dealing with one of the five issues below.

Issue #1: You Bought an Undersized Filter (The GPM Mismatch)

This is the most common mistake I see, and it’s almost always caused by misunderstanding what “GPM rating” actually means.

What happened: That filter you bought is rated for 10 GPM (gallons per minute), but your household actually needs 15 GPM during peak demand. When you run two showers plus the washing machine, you’re forcing water through a filter that can’t handle that flow rate. The result? Significant pressure drop.

How to diagnose it: Install pressure gauges before and after your filter. Open multiple fixtures simultaneously (two showers, one sink, dishwasher). If the pressure drop exceeds 10 PSI during this peak demand test, your filter is undersized.

The fix: You need to calculate your actual peak demand. Here’s the formula I use:

(Number of bathrooms × 6 GPM) + (Kitchen × 3 GPM) + (Laundry × 4 GPM) = Required GPM

For a 3-bathroom home with standard appliances, you’re looking at a minimum 15 GPM filter—not the 10 GPM unit most big-box stores push.

Pro Tip: Flow rate specifications can be misleading. When manufacturers list “15 GPM,” they often mean that’s the maximum the unit can physically handle, not the rate at which it maintains optimal filtration. Look for the “service flow rate” in the installation manual—this is the realistic number. I’ve seen units rated at 12 GPM that specify a 7 GPM service flow in the fine print.

Issue #2: Your Sediment Pre-Filter Is Already Clogged

If your pressure was fine for the first few days or weeks but has gradually declined, you’re almost certainly dealing with sediment accumulation.

What happened: Whole-house filters typically use a 5-micron or 20-micron sediment pre-filter to catch rust, sand, and particulates before they reach the main carbon filter. If your municipal water has high sediment levels—or if you’re on well water—this pre-filter can clog in as little as 2-4 weeks rather than the advertised 3-6 months.

How to diagnose it: Shut off your water supply and remove the sediment filter housing (you’ll need a filter wrench for most units). If the white pleated filter is brown, rust-colored, or visibly packed with debris, that’s your problem.

The fix: Replace the sediment cartridge. But here’s the critical insight: if your filter clogged in under a month, you need a larger sediment filter housing or a lower micron rating. I recommend upgrading to a “big blue” 20-inch housing if you’re currently using a standard 10-inch. The increased surface area dramatically extends filter life.

Warning: Some installers skip the sediment pre-filter entirely to save $40. This is a catastrophic mistake. Without sediment filtration, your expensive carbon media will channel (see Issue #3) within months instead of years. Always use a sediment stage.

Issue #3: Carbon Media Channeling (The Hidden Performance Killer)

This is the issue most homeowners—and even some installers—don’t know about. It’s also the hardest to diagnose without opening your filter tank.

What happened: Inside your carbon filter tank, water should flow evenly through the entire bed of carbon media. When channeling occurs, water creates preferential pathways through the media, flowing through the same channels repeatedly while bypassing the rest of the carbon. This causes two problems: reduced filtration effectiveness and increased resistance (pressure drop).

Why it happens: According to research from the Water Quality Association, channeling is typically caused by:

- Sediment contamination that wasn’t caught by a pre-filter

- Improper backwashing (for backwashing systems) that compacted the media

- Air pockets in the tank from incorrect initial startup

- Low-quality carbon that degraded into fine particles

How to diagnose it: This requires pressure testing at multiple points. Install a gauge before the filter and after the filter. If the pressure differential is high (10+ PSI) but you recently replaced your filters, channeling is likely. The definitive test requires opening the tank—if you see visible pathways or grooves in the carbon bed, or if the media is significantly compacted, you have channeling.

The fix: You’ll need to replace the carbon media entirely. For tank-based systems like SpringWell or Pelican, this means purchasing replacement media (typically 1-2 cubic feet of catalytic carbon). During reinstallation, follow the manufacturer’s backwash procedure exactly—this fluffs the media and prevents immediate re-channeling.

Cost reality: Replacement carbon media runs $100-200 depending on tank size, plus 2-3 hours of DIY labor. If your system is under warranty and channeling occurred within the first year, contact the manufacturer—this is often covered.

Issue #4: The Bypass Valve Is Partially Closed

This sounds embarrassingly simple, but I’ve personally seen this mistake three times in YouTube installation videos from homeowners.

What happened: Most whole-house filters include a bypass valve that allows you to divert water around the filter for maintenance or emergencies. If this valve is even partially open during normal operation, it creates a flow restriction that mimics a pressure drop.

How to diagnose it: Locate your bypass valve (usually a three-way valve near the filter head). It should be in the “service” position, directing all water through the filter. If the valve handle is anywhere between service and bypass, you’ve found your problem.

The fix: Rotate the valve fully to the service position. Your pressure should immediately return to normal.

Issue #5: Internal Filter Damage or Defective O-Rings

Sometimes the issue isn’t your water or your installation—it’s a manufacturing defect.

What happened: The filter housing contains large O-rings that create watertight seals. If these O-rings are pinched during installation, damaged, or defective, water will leak internally. This doesn’t always create visible external leaks, but it dramatically reduces pressure at the tap.

How to diagnose it: Inspect the filter housing during your next cartridge change. Look for:

- Cracked or flattened O-rings

- Water stains inside the housing (indicates internal leakage)

- Loose filter head connection (should be hand-tight plus 1/4 turn with a wrench)

The fix: Replace the O-rings (most manufacturers sell replacement O-ring kits for $10-15). Apply silicone grease to the new O-rings before installation—this prevents pinching and extends O-ring life.

Did You Know? The most common O-ring failure point is over-tightening. According to the Water Quality Association’s installation standards, filter housings should be tightened to hand-tight plus only 1/4 to 1/2 turn with a wrench. Over-tightening crushes the O-ring and guarantees failure.

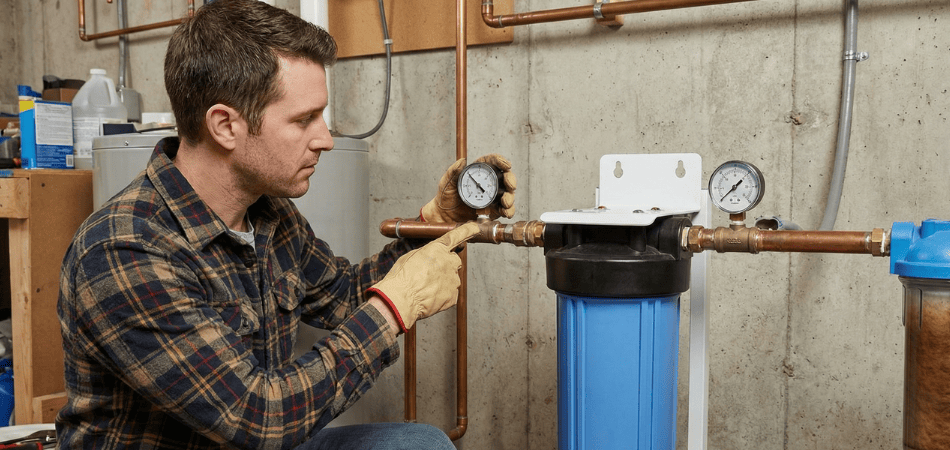

The 10-Minute Diagnostic Protocol

Here’s my step-by-step process for identifying your specific issue:

Step 1: Install a pressure gauge on a hose bib before your filter (the main line). Record the pressure. Normal = 40-60 PSI.

Step 2: Install a second gauge after your filter. Run water through a single fixture. Calculate the pressure drop (Before PSI – After PSI = Drop).

Step 3: Interpret your results:

- 2-5 PSI drop: Normal operation

- 6-10 PSI drop: Check sediment pre-filter; replace if dirty

- 10-15 PSI drop: Filter is likely undersized or pre-filter is severely clogged

- 15+ PSI drop: Probable channeling, internal leak, or bypass valve issue

Step 4: Run the peak demand test (multiple fixtures). If pressure drop exceeds 15 PSI during peak demand, your filter is definitely undersized.

When Professional Help Is Worth It

I’m a strong advocate for DIY troubleshooting, but there are scenarios where calling a licensed plumber saves you time and prevents expensive mistakes:

Call a pro if:

- You have a backwashing system and don’t understand the regeneration cycle

- Pressure issues persist after replacing all filters and checking bypass valves

- You suspect channeling but aren’t comfortable opening your filter tank

- Your pressure drop is accompanied by strange noises (whistling, banging)

Expect to pay $150-250 for a diagnostic service call. A good plumber should test pressure, inspect your installation, and provide written recommendations.

The Cost-of-Ownership Truth

Here’s what most retailers won’t tell you: that $300 whole-house filter with cheap annual filter replacements might cost you $800 more over five years than a $600 system with efficient media.

Calculate before you buy: Annual filter replacement cost is more important than upfront price. A system requiring $150/year in cartridges will cost $750 over five years. A higher-end system with $50/year media replacement costs $250 over the same period—a $500 difference that more than justifies the higher initial investment.

The Bottom Line

Water pressure drops after filter installation are almost always caused by one of five issues: undersized GPM rating, clogged sediment pre-filters, carbon media channeling, partially closed bypass valves, or defective O-rings. The pressure gauge test I outlined above will identify your specific problem in under 10 minutes.

The most common mistake I see is homeowners buying undersized filters based on misleading marketing. A 3-bathroom home needs a minimum 15 GPM service flow rate—not the 8-10 GPM units that dominate big-box store shelves. When in doubt, size up.

If you’re still experiencing pressure issues after working through this guide, the problem may be upstream of your filter (municipal supply issues, pressure regulator failure, or corroded pipes). In those cases, your filter is simply revealing an existing problem rather than creating a new one.